Fit vs Physically Active

One of my graduate assistant roles at the University of Alberta was to conduct fitness tests for the Faculty’s Fitness Testing Unit. The Unit targeted the general population and their health and wellbeing and was well subscribed. We followed standardised fitness testing protocols that included skinfolds, a bike test to estimate aerobic fitness, a sit and reach for flexibility and from memory sit ups, push ups and grip strength to look at muscular performance. The thinking was that clients would be motivated to exercise more by their test results.

In retrospect, what we did with the results was cringeworthy. While the clients went off and showered and changed, we calculated the results and then used normative data tables to score the individual on each test item. This provided an overall fitness profile. A person’s four skinfold measurements would be converted into an estimate of percentage body fat and then compared with others from their gender and age range. So… I found myself frequently telling people that they were in the ‘overfat’ (sorry, that’s what our charts termed it!) category and were in the 10th percentile. This meant that for a hundred people in their age group, they would be in the bottom 10. We then calculated (based on their current weight and estimated body composition) what their weight would be if they were in the above average category (70th percentile) for their age group. If you’ve followed what I have written in the last two sentences, there are all sorts of things wrong with that supposed logic and thinking. Without going into the detail, we’ve got a bunch of dubious measures, assumptions, and interpretations. As a young student, I could sense the changing body language, the slumping bodies, and read the facial expressions, all of which told me that all of this wasn’t really helping at all. Eroding their self-esteem, destroying their self-confidence and belief in exercise clearly wasn’t useful! Unfortunately, I didn’t have the insight or ability to break from the routine that we’d been taught. I was firmly in a mindset, that if these people simply exercised more they would be getting more acceptable results.

As I clocked up more fitness tests and began to shift my focus, I started to recognise a pattern where clients would come to the assessment maintaining that they either were highly active or highly inactive. The trouble was that our testing often suggested the exact opposite. Here’s somebody telling me that they are pretty active and that they do a fair amount of exercise, and yet they test below average for aerobic fitness and fatness. Then, more disturbingly, here’s someone else owning up to doing no exercise and yet somehow their results placed them high on the percentiles for fitness. You just try to motivate either one of those clients with those contradictory test results!!

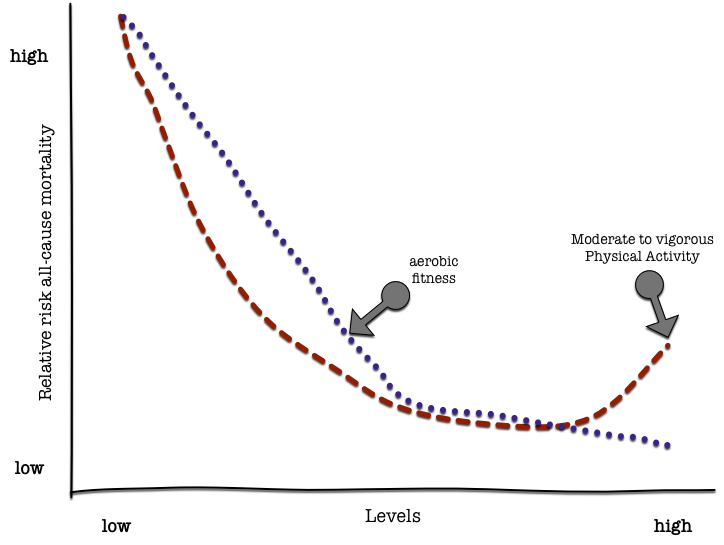

As I started to reflect on what I was seeing and experiencing, I started to rationalise that fitness and physical activity were not necessarily closely linked. That was sacrilege for a sports science graduate, but I couldn’t figure it any other way. Either the clients were lying or the tests were useless. Without any evidence, I started to change my story and explain that physical activity was a habit (and a darn good one, we thought). You could be physically active and although you may not see their results in terms of weight loss and test scores, you were still benefitting. Fitness was more an attribute – sure you could influence it with exercise, but some were born with naturally good fitness and leaner bodies, despite their nutritional and activity habits. Turns out that wasn’t too far from the truth. Bouchard et al (2015) reviewed the protective effects of physical activity (the habit) and compared them with aerobic fitness levels (the attribute). Here’s a rough graph of their findings. The vertical axis is effectively ‘risk of death’ and the horizontal axis is the amount of activity or aerobic fitness. As you can see the habit of being physically active offers protection, independent of fitness level and here’s the good news, that protection appears to be at all levels of body weight. Clearly, the experts haven’t really untangled the complex relationship between physical activity, fitness, fatness, and health. Bouchard et al (2015) think we need to be able to differentiate between what they term ‘intrinsic’ and ‘acquired’ aerobic fitness, to understand the benefits more clearly. I guess the message I’d like everyone to get out of this is that measures of fitness might be important but may not be something that all of us can change dramatically or promptly. To me, the habit of being physically active not only seems to help health but also has so much more to offer. I beg you – please don’t be discouraged if the numbers don’t budge or don’t move very quickly.

Best, Phil