Was I right?

Closed Chain Exercises Minds

1139 words – estimated reading time: 4 min, 56 sec

Full disclosure, this is an ‘I told you so’ blog. Despite my ongoing rants and critiques, I’ve rarely been proven right – sigh!!!.

Back in the late 1980s and early 90s most of my work was in exercise rehabilitation. I loved that work and still have an interest. The satisfaction when a client successfully returned to training and competition, was something that rarely experienced working in strength and conditioning or exercise and health. Somehow those clients always wanted more – more speed, more weight loss! Even though I started out working in a sports medicine clinic, I discovered rest of the local physio community were not overly excited to have someone like me in the neighbourhood. In fact, most tried to discredit my work, suggesting that I was not appropriately trained and therefore couldn’t possibly know what I was doing. This conveniently overlooked that my 4-year physical education degree and my 2-year Master’s degree in Exercise Rehabilitation (Alberta), was bit more than their 3-year physiotherapy diplomas, and included significantly more exercise knowledge and experience.

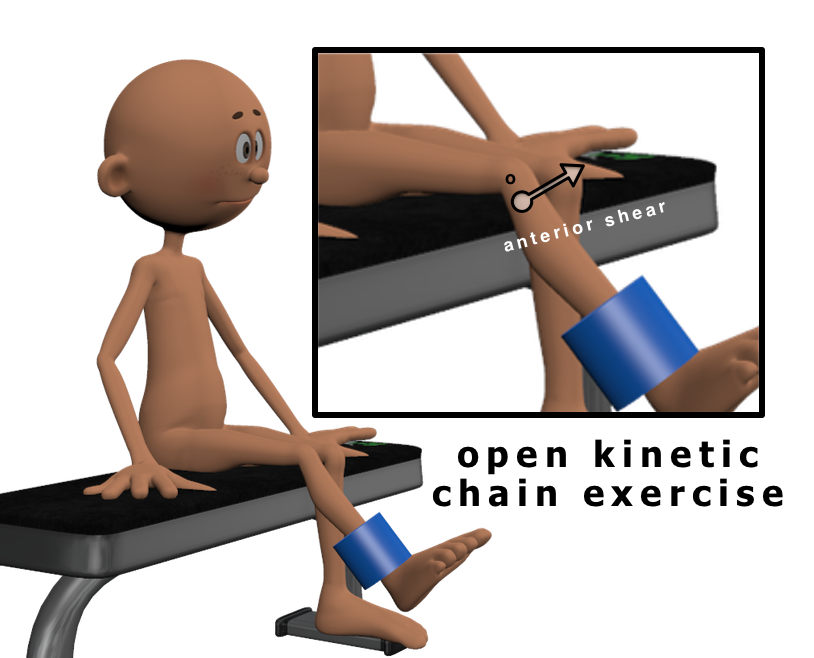

Their main gripe was that I used ‘open kinetic chain’ (OKC) leg extension exercises as part of the rehabilitation of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injured clients. Apparently EVERYONE KNEW that OKC exercises were contraindicated as they supposedly produced anterior shear at the knee and could stretch a healing or reconstructed ACL. Instead ACL rehabilitation was supposed to be almost exclusively closed kinetic chain (CKC), certainly through until a return to play.

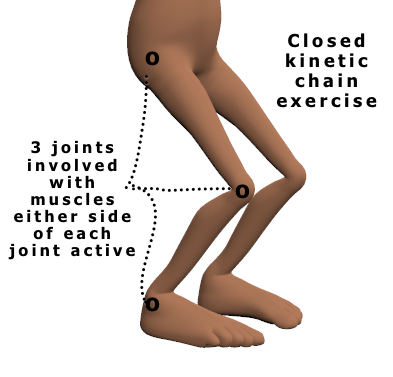

A closed kinetic chain describes a movement where the terminal/distal segment meets significant external resistance that inhibits free movement of those segments (see figure 2). As neither the proximal nor the distal segments can move freely in a CKC, if one segment moves, all other segments and joints will also have to move in some way. Compare a chin up and a simple arm curl exercise. For the arm curl, the elbow joint flexes and extends and is for all intents and purposes the only joint involved. In the chin up, the wrist and hand are attached (fixed) to the bar through a grip. If we attempt to flex the elbow, the shoulder, scapula, and wrist also have to move and will all involve muscular actions contributing to the chin up. When we attempt to define some actions there are inevitably exceptions to these principles (e.g. throwing a javelin, putting a shot, walking on a stair machine) – probably why these terms have therefore become increasingly less popular.

Back to ACL injury – in the mid-1980s the New Zealand sports injury industry seized on some research that argued that leg extension exercises produced anterior shear at the knee and could stretch the ACL (e.g. Henning et al., 1985). Physios and others jumped on that bandwagon, seemingly without a lot of critical thought. The anti OKC factions based their opposition on two key points; OKC exercises were dangerous producing excessive anterior shear forces and therefore were likely to stretch an ACL (see Figure 1), and CKC exercises were more functional using multiple joints and muscle groups that helped contribute to joint stability. To my way of thinking, these assumptions were wrong on both accounts.

Having been educated in North America I had been taught me to approach things more critically, and there the views on OKC and CKC exercises were much less polarised. They had taught us how to modify leg extension exercises using basic biomechanical and motor control principles to minimise anterior shear. This provided low risk ways to effectively isolate and strengthen quadriceps. I also knew that the role of co-contracting muscle groups (muscles either side of a joint working simultaneously) in helping stabilise joints was misinterpreted and overstated. Not to say that co-contraction wasn’t important and useful, but that the co-contraction muscle activity required for joint stability was surprisingly low. As lower limb CKC exercises like a squat or leg press involved multiple joints, there seemed to me to be potential for the stronger, healthier joints and muscles to make up for, and compensate for, the weak knee extensors. I thought that with such substitution, the knee extensors during CKC exercises were unlikely to be optimally stimulated for strength improvements.

Even after moving out of the rehabilitation space, I continue to follow research on OKC and CKC exercise. Working in tertiary education, I regularly saw students rehabbing from ACL injury, and was disappointed to see that the anti-OKC ideology was still prevalent in physical therapy, and that this flawed rhetoric persisted at local sports medicine conferences. With access to isokinetic testing, we routinely demonstrated large quadriceps strength deficits in individuals who had worked through lengthy CKC rehabilitation protocols! So their quads strength had not been restored and yet they were suggested to be ready to return to play.

I have since learned why individuals (and selected professions) think they way that they think, and why they passive aggressively persist in defending their stances and disparaging contrary opinions and the work of others. These examples of cognitive dissonance show that arguments, logic and research evidence counter to one’s firmly held beliefs are rarely critically integrated into thinking and practice. Of course I’m as guilty of doing the exact same thing in pursuing research supporting my beliefs around CKC exercise. That said, Noehren and Snyder- Mackler (2020) shred the flawed premises of the CKC exclusive/dominant rehabilitation bandwagon and I think bury it for good. They state that [the] “… fear of loosening the healing graft has become so ingrained that contemporary clinicians often accept this disproven fear as fact… “(p. 473). This ongoing misinformation and ‘old school’ concerns about the safety of open-chain exercises are direct obstacles to improving quadriceps strength in ACL injured individuals. By stubbornly defending a CKC only stance, therapists are often returning individuals to sport with large quadriceps strength deficits. Closed-chain exercises alone do little to rectify the quadriceps weakness that may persist for up to 2 years after rehabilitation (Lepley, 2015; Toole et al., 2017). In my view that stubbornness translates into professional negligence. A progressive programme that includes both OKC and CKC is more likely to optimise strength and prepare injured individuals for functional rehabilitation and a successful return to play.

I think the OKC vs CKC debate offers many learning moments for exercise professionals, all of which highlight the absolute need for continued critical thinking. As an exercise professional, being willing and able to break down the logic and scientific rationales informing a particular method or ideology is my primary measure of acting as a ‘professional’. I am less interested in what you know – rather that you recognise that knowledge is transitory, and that you will be constantly reexamining, updating, and if necessary correcting your practice.

Best, Phil

References:

- Henning, C.E., Lynch, M.A., Click, K.R. (1985) An in vivo strain gage study of elongation of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am. J. Sports Med., 13: 22-26.

- Lepley, L.K. (2015) Deficits in quadriceps strength and patient-oriented outcomes at return to activity after ACL reconstruction: a review of the current literature. Sports Health. 7:231-238.

- Noehren, B., Snyder-Mackler, L. (2020) Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? Open-Chain Exercises After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Journal Of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 50 (9):473 – 476

- Perriman, A., Leahy, E., Semciw, A.I. (2018) The Effect of Open- Versus Closed-Kinetic-Chain Exercises on Anterior Tibial Laxity, Strength, and Function Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 48:7, 552-566

- Steindler, A. (1977) Kinesiology of the Human Body Under Normal & Pathological Conditions, Thomas, Springfield, ILL.

- Toole, A. R., Ithurburn, M. P., Rauh, M. J. et al. (2017). Young athletes cleared for sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: how many actually meet recommended return-to-sport criterion cutoffs? Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 47(11), 825-833.

September 2, 2021 @ 11:32 pm

Interesting article Phil,

I personally learned that “OKC strengthening is harmful in ACL recovery” about 3-4 years into my Physio career from some senior Physios who ran knee rehab training. Somehow I missed that in Physio school. Anyway after removing OKC exercises from my ACL rehab I did notice quad strength improvement was slower and return to play took longer.

What I find interesting though, is I followed the advice of the senior Physios completely uncritically. I didn’t research the claims whatsoever. I just provided less effective (but I guess I hoped safer) rehab for the rest of my (somewhat short lived) Physio career.

It’s funny that we (or at least I) have to be constantly reminded to reflect on our assumptions. So cheers for the mental kick up the bum.

September 2, 2021 @ 11:37 pm

Thanks Pat – we are all guilty of exactly that. I cringe when I recall some of the things that I accepted as gospel and that I recounted to clients. I guess tertiary education is often guilty of turning out graduates who are not geared for critical thinking. Best, Phil