Do As I Say

So much information!!!

Could I have been that arrogant, that stupid? Turns out yes I could – in spades! In fairness, I’d been raised on a steady educational diet

where knowledge was king; knowledge was power. It never occurred to me that it could be any other way. Certainly, none of my teachers or lecturers had ever hinted otherwise, so my belief was deeply ingrained. Unfortunately, that attitude never wavered through my first 8 years of practice. Regardless of my work context; general health and fitness, exercise rehabilitation of athletic injuries, or rugby strength and conditioning, when people failed to do their prescribed training or exercise, it was their fault. By not accepting and following my advice these people had to be stupid, lazy and/or irrational. The thing was that some people actually did follow my advice and experience success, enough to camouflage the reality. So I had no real cause to pull my head out of the sand and reflect on my practices. Obviously, I was doing a great job – now if only I could get those others to listen!

Why didn’t somebody tell me this?

When I moved into academia, I’m ashamed to say those attitudes also went with me and informed my teaching for my first 3 or 4 years. It was only when I developed practicums to run alongside my exercise prescription papers, that the penny dropped. With the opportunity to stand outside of practice and observe some of my students engaging in the same work that I’d been doing, I started to notice things differently. I was seeing that there were some significant discrepancies between theory and practice. What was supposed to work, often didn’t, and what was supposed to not be effective, often was. In those settings, I could observe the demeanour and approaches of the students as they interacted with clients, and begin to take a bit more notice of client body language. I could see how certain statements affected them, and how they subtly indicated their trust, beliefs, and expectations. But the most disarming thing was how such seemingly well- formulated and well-communicated advice and instruction, so often failed to result in changes in exercise behaviours.

Were people not changing their behaviours because they didn’t know what to do, or were there other reasons? It seemed to me that the approach we as exercise professionals subscribe to is, ‘if we clearly explain to them what to do, they’ll do it’. As exercise professionals, we are often encouraged to think of ourselves as teachers. We certainly instruct, coach, assess and provide continual feedback, but we are also educating people on how to take charge of their physical activity when we are not there for support. Setting them up to run their own exercise programmes in the gym and at home, take care of their injuries, or training for their sport. I guess there’s the trap – because while education may be part of the process it is not always the solution.

Is exercise literacy really a thing?

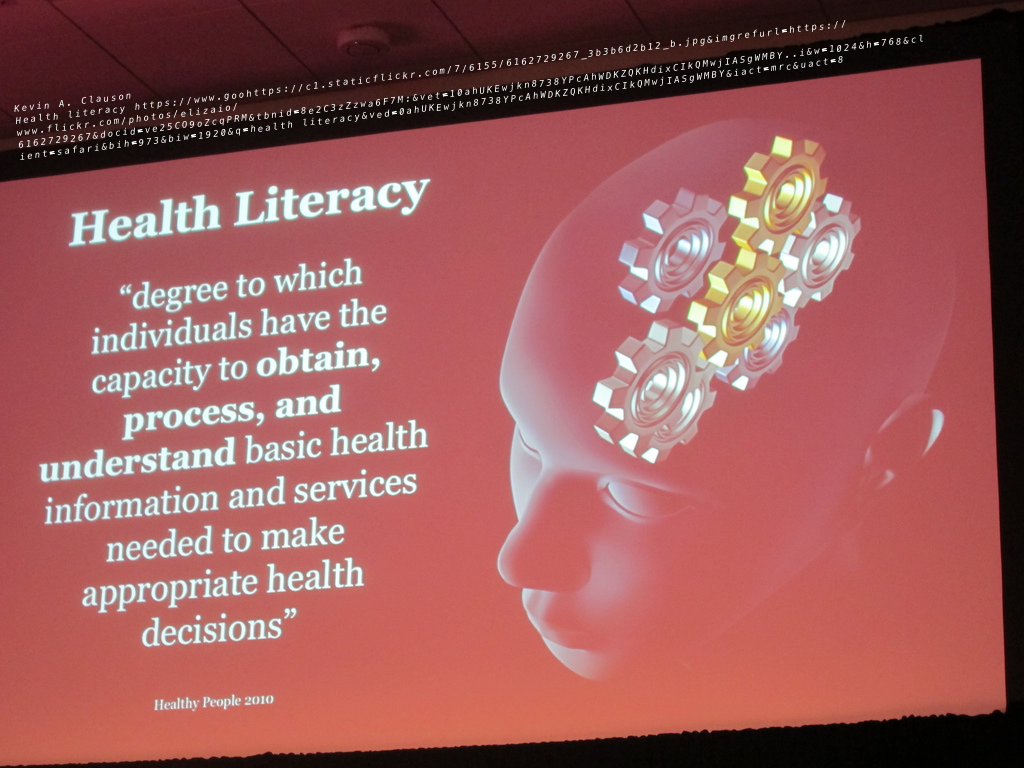

The concept of health literacy has been around since the late 1990s and has been used to describe the ability to gain access to, understand, evaluate and communicate health information required to engage successfully with various health contexts, services and behaviours (Goebers et al, 2014).

While it’s easy to believe the health illiteracy is the root cause of inactivity (see most physical activity and health initiatives), this is likely

just one of several complexly interacting factors. Goebers et al (2014) explored the relationship between health literacy and nutritional and physical activity behaviours in older adults, finding a marginally significant association between inadequate health literacy and physical inactivity. The thing that seemed to help convert literacy into moreactive behaviours was self-efficacy. Focusing on building individual’s exercise confidence and belief in their own abilities may, therefore, be a key target for interventions.

There’s comfort in those assumptions

Kelly and Barker (2016) argue that we often leap into interventions with some largely incorrect assumptions. We make the mistake of considering behaviour change as something relatively straightforward and common sense. In doing this we tend to privilege knowledge and information and perpetuate our own belief that knowledge drives behaviours such as how people eat, drink and exercise. In many ways, we seem to be stuck with a reverence for messaging as the way to drive useful information to populations. I’ve been very critical of public health messaging particularly around physical activity and health for taking this kind of approach. It seems to me that those initiatives have failed on so many levels. From my perspective exercise professionals are dealing with people, not populations! Realising that behaviours are often socially determined, I’d probably now rephrase that to state that we are dealing with people and their contexts, not populations. The ‘one size fits all’ messaging does not really individualise the information, the timing, or the setting for information sharing to suit individual contexts. Not only are so many of those public health initiatives having minimal (if any) impact on physical activity levels, but it really grates that they routinely seek to change behaviours by labeling, blaming and shaming people into becoming more physically active. Slightly off topic but …. something that I always notice is how exiled smokers seem to share an instant bond when their habits are outed. While cognitively they may know that smoking is not a wise choice, the method of forcing a change in the behaviour obviously rankles.

Two of the assumptions listed by Kelly and Barker (2016) really resonated with me. They suggest that we frequently assume that people are rational and people are irrational in responding to exercise information and messaging. Let me explain; the assumptions are that when presented with appropriate information concerning health behaviours (e.g. smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise and diet) that people will judiciously analyse thatadvice and then follow up by doing the sensible and logical thing – entirely rational behaviour. If armed with that information people however still fail to act sensibly and logically, they are demonstrating irrational behaviour. The points that Kelly and Barker (2016) are making are that these people are neither rational nor irrational. People in fact have reasons for sticking to a particular behaviour. We may not agree with those reasons but those reasons will be very rational to them.

For example, there will be reasons why inactivity will be the option preferred over activity. Inactivity is often engrained in peoples lives, it may be part of their everyday routines and a firmly embedded behaviour within their social circle. An individual may in fact be surrounded by a lot of positive cues that reinforce sedentary behaviours over physical activity, that will make increased activity challenging. So according to Kelly and Barker (2016) there is no reason to expect people to (according to our point of view) behave rationally. And if they fail to do so, they are not necessarily acting irrationally – they will have reasons that are rational to them. Going back to my smoking example, through a different lens you could maybe see that smoking may be socially acceptable within a circle of co-workers, friends or family. It may be the only relaxing time in a day for them, something to occupy their hands, or something that soothes them. Without endorsing smoking, these are rational reasons.

A competent exercise professional…

The challenge for the exercise professional then is to find ways to treat each client as unique and try to avoid making assumptions about their behaviours or ease of change. The more that we communicate with and understand clients, the closer we edge towards solving the behaviour change challenge. Perhaps taking the extra time and making the effort to understand an individual’s context before we turn on the knowledge tap, will help us reflect on our practices. Sharing evidence-based information is an art that needs to take contextual conditions into account.

Best, Phil

Selected references

- Geboers, B., De Winter, A.F., Luten, K.A., Jansen, C.J.M., Reijneveld, S.A. (2014) The Association of Health Literacy with Physical Activity and Nutritional Behavior in Older Adults, and Its Social Cognitive Mediators. Journal of Health Communication 19:61–76.

- Guntzviller, L.M, King, A.J., Jensen, J.D., Davis, L.A. (2017) Self-Efficacy, Health Literacy, and Nutrition and Exercise Behaviors in a Low-Income, Hispanic Population. J Immigrant Minority Health 19:489–493.

- Kelly, M.P., Barker, M. (2016) Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 136;109–116.

- Nutbeam, D. (2000) Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health. Health Promotion International 15(3); 259 – 267.

- Ratzan, S.C. (2001) Health literacy: communication for the public good. Health Promotion International 16 (2); 207- 214